|

| Edward the Confessor |

Total Pageviews

Saturday, 22 September 2012

Tuesday, 19 June 2012

Friday, 15 June 2012

The Story: Scene 2

Interpreting The Tapestry: Scene

by Scene

Scene 2

I personally prefer to follow the story that Harold crossed the sea to Normandy with the sole intention of bringing home his relatives, Hakon and Wulfnoth. Mainly because this seems the most feesible rationale for him going and Eadmer, albeit a later chronicler, confirms it. I do not think that Edward had decided to send Harold on a mission to pass on his blessing and offer him the crown at all. Why would he endow his great nephew Edgar with the title of Atheling if he had intended William for the crown all along. And William was never referred to as Atheling or the heir to the English throne prior to his taking it. So imagine Harold arrives at the court of Normandy only to find that the Duke has ideas about his arrival there of his own.

So why did William believe he was the King of England's heir? He was not of the line of the Kings of Wessex and there were others who might have been more qualified after all. Edward had his nephews, Ralph who died in 1057 and would have been out of the running by the 1060's, and Walter de Mantes who dies in the captivity of the Duke of Normandy along with his wife. Young Edgar the Atheling, grandson of Edward's older brother Edmund Ironside. Edgar would have had a far better claim than William. A clue, in fact, lies in the Anglo Saxon chronicle. Chronicle D claims that in the entry for 1051, Duke William came with a large contingent of 'French' men and was recieved by King Edward. It says no more than a few cursory words and says nothing about discussing the succession with him. Historians have been known to wrangle over the validity of this claim as it is only mentioned in Chronicle D and not any of the others. Some have suggested that this possibly never happened and was a late entry to help promote William's actions as justifiable. It has been noted that there were reasons to believe that this visit did not take place: one of them is that it was likely that William's difficulties in Normandy at this time would have made it impossible for him to come to England and it is curious as to why contemporary Norman sources made no note of it either. However later, it was claimed that in this meeting, (as goes the Norman propaganda machine) that the offer of an heirdom took place. So, if we look at the previous events, it is plausible to imagine that scenario did take place and let's face it,William cannot have plucked the idea out of thin air. There must have been some basis for it.

So why did William believe he was the King of England's heir? He was not of the line of the Kings of Wessex and there were others who might have been more qualified after all. Edward had his nephews, Ralph who died in 1057 and would have been out of the running by the 1060's, and Walter de Mantes who dies in the captivity of the Duke of Normandy along with his wife. Young Edgar the Atheling, grandson of Edward's older brother Edmund Ironside. Edgar would have had a far better claim than William. A clue, in fact, lies in the Anglo Saxon chronicle. Chronicle D claims that in the entry for 1051, Duke William came with a large contingent of 'French' men and was recieved by King Edward. It says no more than a few cursory words and says nothing about discussing the succession with him. Historians have been known to wrangle over the validity of this claim as it is only mentioned in Chronicle D and not any of the others. Some have suggested that this possibly never happened and was a late entry to help promote William's actions as justifiable. It has been noted that there were reasons to believe that this visit did not take place: one of them is that it was likely that William's difficulties in Normandy at this time would have made it impossible for him to come to England and it is curious as to why contemporary Norman sources made no note of it either. However later, it was claimed that in this meeting, (as goes the Norman propaganda machine) that the offer of an heirdom took place. So, if we look at the previous events, it is plausible to imagine that scenario did take place and let's face it,William cannot have plucked the idea out of thin air. There must have been some basis for it.

So what did happen before William's visit to his second cousin in 1051? This is the back-story according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicles: At mid-lent, 1051, as there was now a vacancy for the Archbishop of Canterbury's job, Edward called his council-meeting in London and advised them of his wish that his great friend and advisor, Robert Champart, former Abbot of Jumieges, should be given that post. It seems that Robert Champart may have put some noses out of joint when he came back from Rome with his pallium, because when Bishop Spearhavoc, whom Edward had promoted to Robert's see of London, approached him with the King's writ, Robert refused to consecrated him stating that the Pope had refused to let him do this. Spearhavoc was an outstanding artist whose engravings and paintings had brought him to the attention of the Godwins and the King. He may have been closely allied with the Queen. Why the Pope was against him being consecrated seems to be unknown and Robert was not about to go against the Pope in this just after recieving his pallium.

What follows appears to be a chain of events that may well be linked together. Count Eustace of Boulogne, brother-in-law of King Edward for his marriage to Goda, Edward's sister, came across the sea to visit with Edward. Chronicle E states that he

".....he turned to the king and spoke with him about what he wanted, and

then turned homeward....when he was some miles or more this side of Dover,

he put on his mail coat and all his companions and went to Dover."

This sounds like Eustace was looking for trouble. He was and it was to have consequences thereafter for Godwin Earl of Wessex and his family. The men of Dover took a dislike to the way that Eustace and his followers demanded hospitality from them and when one of his men wanted to lodge at the house of a man against his will, the Frenchman attacked and wounded him. He found himself at the end of the householder's rage and the Englishman killed him. A fight in the town ensued after the householder was then killed by Eustace and his men and the French killed 20 townsmen and they themselves lost 19 of their own.

Eustace and his men rode out of Dover to report to the King of the indignities that had been inflicted upon them. Edward was apparently aflame with anger. Now Dover was in the jurisdiction of Earl Godwin and Earl Godwin was a thorn in the King's side. He ordered Godwin to punish Dover by ravaging their homes and Godwin, most likely having heard the side of the townsfolk, refused. Does this actually sound like the pious, gentle Confessor we later know him as?

Edward rallied all his loyal thegns and earls to him and Godwin and his sons did also. There was a standoff and still Godwin refused to punish the men of Dover. Eventually, some of his men deserted him and went over to Edward, probably because they did not wish for there to be a civil war in the country. The Godwins were given a few days to leave. Godwin and his sons Swein,Tostig, Gyrth and his wife Gytha, fled to Bruges. Harold went with his younger brother Leofwine to Bristol and took Swein's ship to Ireland after a storm cost them the lives of some of their follwers. It was around this time that the Godwin boys Hakon and Wulfnoth were most likely handed over to the King as hostages.

This event would also have a negative consequence for the Queen, (who was also a Godwin) and perhaps the priestly goldsmith, Spearhavoc. The Queen was stripped of all her wealth and banished to a nunnery, although she had evaded this for awhile. Robert most likely urged him to put her away for being a Godwin, and urged the King to look elsewhere for a wife. As for Spearhavoc, it could be that Robert knew something about his character that others didn't, for after carrying out his duties in the see for months with Edward's permission and without consecration, according to the Chronicle E, Spearhavoc was then driven out of the bishopric; but not before, according to the Historia Ecclesie Abbendonensis, he gathered all the gold and jewels he had been comissioned with from the King to fashion some regalia for him, in many bags and made off abroad with them never to be seen again. Perhaps his patrons Godwin and Queen Edith had argued with Robert Champart against expelling Spearhavoc from the bishopric and this might have annoyed the King immensely, stuck in the middle between them and his great friend Robert. He already had no particular liking for Godwin, for he still held Godwin responsible for the death of his brother Alfred over 15 years ago. When Eustace arrives back to the scene, perhaps they concocted an elaborate plot to stir Godwin into defiance and give the king a good reason to be rid of him at last.

Please feel free to ask any questions of me and my theories.

Hope you have enjoyed the journey through the Bayeux Tapestry so far and will continue through this amazing journey.

Scene 2

A

And so Harold and his men arrive at Bosham. As previously discussed in my first post examining the BT scene by scene, Harold is off to Normandy to pay the Duke a visit and discuss terms for the release of his kin, however if we are looking at it from the Norman's point of view, Harold was on a misssion, sent by King Edward, to confirm his succession to the English crown upon Edward's death. Edward had been playing fools advocate for years it would seem, dangling the crown in front of various contenders. At the time of Harold's trip to Normandy, the Earl was at the height of his power, a man in his early forties, well experienced in diplomacy and administration as well as campaigning against the Welsh. He had recently put an end to King Gruffydd's harrassment of English lands along the borders by embarking on an invasion of Wales of the like he had not attempted before. In a joint enterprise with Tostig, his brother, Earl of Northumberland, he marched his army into the stonghold of Rhuddlan, forcing Gruffydd to flee into the wilds of Snowdonia whilst Harold, harrying the Welsh until they themselves murdered Gruffydd, sending his head to Harold as proof.I personally prefer to follow the story that Harold crossed the sea to Normandy with the sole intention of bringing home his relatives, Hakon and Wulfnoth. Mainly because this seems the most feesible rationale for him going and Eadmer, albeit a later chronicler, confirms it. I do not think that Edward had decided to send Harold on a mission to pass on his blessing and offer him the crown at all. Why would he endow his great nephew Edgar with the title of Atheling if he had intended William for the crown all along. And William was never referred to as Atheling or the heir to the English throne prior to his taking it. So imagine Harold arrives at the court of Normandy only to find that the Duke has ideas about his arrival there of his own.

So what did happen before William's visit to his second cousin in 1051? This is the back-story according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicles: At mid-lent, 1051, as there was now a vacancy for the Archbishop of Canterbury's job, Edward called his council-meeting in London and advised them of his wish that his great friend and advisor, Robert Champart, former Abbot of Jumieges, should be given that post. It seems that Robert Champart may have put some noses out of joint when he came back from Rome with his pallium, because when Bishop Spearhavoc, whom Edward had promoted to Robert's see of London, approached him with the King's writ, Robert refused to consecrated him stating that the Pope had refused to let him do this. Spearhavoc was an outstanding artist whose engravings and paintings had brought him to the attention of the Godwins and the King. He may have been closely allied with the Queen. Why the Pope was against him being consecrated seems to be unknown and Robert was not about to go against the Pope in this just after recieving his pallium.

What follows appears to be a chain of events that may well be linked together. Count Eustace of Boulogne, brother-in-law of King Edward for his marriage to Goda, Edward's sister, came across the sea to visit with Edward. Chronicle E states that he

".....he turned to the king and spoke with him about what he wanted, and

then turned homeward....when he was some miles or more this side of Dover,

he put on his mail coat and all his companions and went to Dover."

This sounds like Eustace was looking for trouble. He was and it was to have consequences thereafter for Godwin Earl of Wessex and his family. The men of Dover took a dislike to the way that Eustace and his followers demanded hospitality from them and when one of his men wanted to lodge at the house of a man against his will, the Frenchman attacked and wounded him. He found himself at the end of the householder's rage and the Englishman killed him. A fight in the town ensued after the householder was then killed by Eustace and his men and the French killed 20 townsmen and they themselves lost 19 of their own.

Eustace and his men rode out of Dover to report to the King of the indignities that had been inflicted upon them. Edward was apparently aflame with anger. Now Dover was in the jurisdiction of Earl Godwin and Earl Godwin was a thorn in the King's side. He ordered Godwin to punish Dover by ravaging their homes and Godwin, most likely having heard the side of the townsfolk, refused. Does this actually sound like the pious, gentle Confessor we later know him as?

Edward rallied all his loyal thegns and earls to him and Godwin and his sons did also. There was a standoff and still Godwin refused to punish the men of Dover. Eventually, some of his men deserted him and went over to Edward, probably because they did not wish for there to be a civil war in the country. The Godwins were given a few days to leave. Godwin and his sons Swein,Tostig, Gyrth and his wife Gytha, fled to Bruges. Harold went with his younger brother Leofwine to Bristol and took Swein's ship to Ireland after a storm cost them the lives of some of their follwers. It was around this time that the Godwin boys Hakon and Wulfnoth were most likely handed over to the King as hostages.

This event would also have a negative consequence for the Queen, (who was also a Godwin) and perhaps the priestly goldsmith, Spearhavoc. The Queen was stripped of all her wealth and banished to a nunnery, although she had evaded this for awhile. Robert most likely urged him to put her away for being a Godwin, and urged the King to look elsewhere for a wife. As for Spearhavoc, it could be that Robert knew something about his character that others didn't, for after carrying out his duties in the see for months with Edward's permission and without consecration, according to the Chronicle E, Spearhavoc was then driven out of the bishopric; but not before, according to the Historia Ecclesie Abbendonensis, he gathered all the gold and jewels he had been comissioned with from the King to fashion some regalia for him, in many bags and made off abroad with them never to be seen again. Perhaps his patrons Godwin and Queen Edith had argued with Robert Champart against expelling Spearhavoc from the bishopric and this might have annoyed the King immensely, stuck in the middle between them and his great friend Robert. He already had no particular liking for Godwin, for he still held Godwin responsible for the death of his brother Alfred over 15 years ago. When Eustace arrives back to the scene, perhaps they concocted an elaborate plot to stir Godwin into defiance and give the king a good reason to be rid of him at last.

Please feel free to ask any questions of me and my theories.

Hope you have enjoyed the journey through the Bayeux Tapestry so far and will continue through this amazing journey.

A

A

Labels:

atheling,

Bayeux Tapestry,

Dover,

Eadmer,

Edith,

Edward the Confessor,

Eustace of Boulogne,

Gyrth,

Gytha,

Hakon,

Harold Godwinson,

Leofwin,

Swein,

Threads to the Past,

William of Normandy,

Wulfnoth

Thursday, 24 May 2012

The Story

Interpreting The Tapestry Scene by Scene: Scene 1

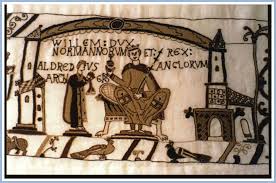

This is scene one of the embroidery. It starts with King Edward, shown resplendent in his palace speaking with two men. One of the men is obviously Harold, probably the taller because the tapestry seeme to show men of lower status as much smaller so perhaps Harold is with his most faithful huscarle or servant. Further on, 6 men are riding out with their hunting animals and the Latin text in the top of the border reads Harold, Duke of England: and his soldiers ride to Bosham.

From what we know of the tale of the embroidery, the Norman sources tell us that Harold was sent to Normandy on a great mission by his brother-in-law the King to convey his good wishes to Duke William and confirm him in the succession. As I have said in my previous post, the English account written by Eadmer tells a different story altogether. It would have us believe that Harold (very much his own man) informs King Edward that he is going on a journey to Normandy to meet with Duke William and negotiate the release of his brother and nephew who have been hostages in Normandy for several years. Edward advises against this mission and tells Harold that only harm can come of it, but Harold takes his leave despite Edward's advice. Either story can be represented in the scene.

Whichever theory you believe, the next scene can have no double meaning. It simply shows Harold and his men riding toward Bosham where he will embark on his journey in one of his ships. He most likely wanted to ride to Bosham to collect some gifts for William. If he was going to Normandy to get his brothers, he would need to make it worth his while.

Bosham was Harold’s father’s manor estate, granted to him by Cnut. It is said that Cnut’s daughter is buried in the church when she slipped and fell into the millstream. This was also where Cnut was said to have proved to his subjects that he was not all powerful by putting his throne on the edge of the beach to show them he couldn’t hold back the tide. Godwine, Harold’s father, made it his family home and most likely the Godwin brothers and sisters grew up there. You can imagine the youngsters playing in the courtyard of their father’s longhall. I can almost hear Swegn, Harold and Tostig arguing amongst themselves, an omen of what was to come later.

Swegn was to grow up to be the black sheep of the family and Tostig would eventually go on to be betrayed by his brother Harold and then he in turn would betray Harold by attempting an invasion with Harald Hardrada. Tostig was killed alongside Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, playing his part in the downfall of Anglo-Saxon England.

This is scene one of the embroidery. It starts with King Edward, shown resplendent in his palace speaking with two men. One of the men is obviously Harold, probably the taller because the tapestry seeme to show men of lower status as much smaller so perhaps Harold is with his most faithful huscarle or servant. Further on, 6 men are riding out with their hunting animals and the Latin text in the top of the border reads Harold, Duke of England: and his soldiers ride to Bosham.

From what we know of the tale of the embroidery, the Norman sources tell us that Harold was sent to Normandy on a great mission by his brother-in-law the King to convey his good wishes to Duke William and confirm him in the succession. As I have said in my previous post, the English account written by Eadmer tells a different story altogether. It would have us believe that Harold (very much his own man) informs King Edward that he is going on a journey to Normandy to meet with Duke William and negotiate the release of his brother and nephew who have been hostages in Normandy for several years. Edward advises against this mission and tells Harold that only harm can come of it, but Harold takes his leave despite Edward's advice. Either story can be represented in the scene.

Whichever theory you believe, the next scene can have no double meaning. It simply shows Harold and his men riding toward Bosham where he will embark on his journey in one of his ships. He most likely wanted to ride to Bosham to collect some gifts for William. If he was going to Normandy to get his brothers, he would need to make it worth his while.

Bosham was Harold’s father’s manor estate, granted to him by Cnut. It is said that Cnut’s daughter is buried in the church when she slipped and fell into the millstream. This was also where Cnut was said to have proved to his subjects that he was not all powerful by putting his throne on the edge of the beach to show them he couldn’t hold back the tide. Godwine, Harold’s father, made it his family home and most likely the Godwin brothers and sisters grew up there. You can imagine the youngsters playing in the courtyard of their father’s longhall. I can almost hear Swegn, Harold and Tostig arguing amongst themselves, an omen of what was to come later.

Swegn was to grow up to be the black sheep of the family and Tostig would eventually go on to be betrayed by his brother Harold and then he in turn would betray Harold by attempting an invasion with Harald Hardrada. Tostig was killed alongside Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, playing his part in the downfall of Anglo-Saxon England.

|

| Bosham |

Wednesday, 9 May 2012

A Tale of Two Boys

The tapestry shows the tale of Harold's journey to Normandy, his imprisonment by Guy de Ponthieu and his subsequent release into the hands of William of Normandy and his adventures there until he is coerced to take an oath to promise to be William's man and when the time comes, assist him to the throne of England. He is released back to England where he is shown accepting the crown himself after the death of Edward. What follows is the great preperation William undertakes to make a large fleet of boats to invade England with, the battle of Hastings and the demise of Harold and defeat of the English. There it stops abruptly but the final scenes are thought to have been damaged and probably concluded with the coronation of the victorious conqueror.

The Norman slant on this story is that Harold was comissioned by Edward to visit William with gifts and offerings to confirm his intention of naming him as heir. The English version was very different. Harold went on a mission to visit William with the sole purpose of negotiating the release of his brother Wulfnoth and nephew Hakon, against the advice of the King who told him that nought would come of it but trouble. This was Eadmer's version, a monk of Canterbury. It seems that Harold eventually returns to England with only one of the men he wanted to release, Hakon. Wulfnoth was to stay in Normandy presumably until William was crowned king. Hakon most likely died with his uncle the King at Hastings.

The two men do not appear in the tapestry by name but in a certain scene, where Harold stands before William, who is seated on his throne as his guest is gesticulating and pointing to the man who stands behind him sporting a beard and an English hairstyle. Because most of the men in the tapestry are either English or Franco/Norman, the distinction between the two races are often marked by such differences as cropped hair above the ears and clean shaven faces for the Normans and moustaches and full heads of hair for the English. Iconography exists quite often in the tapestry to signify a certain point that the artist is making. The chap that Harold appears to be pointing to is standing very much apart from the otherNorman knights behind him. He carries his shield under his arm and Bridgeford 2004 states that the shield is not dissimilar to the one that the Bayeux Tapestry shows Harold holding in the battle scenes. He goes on to make the claim that this is most likely Wulfnoth Godwinson, Harold's brother, the kinsman that it is said he came to plead for his freedom.

So, we have the dilemma. Which version do we believe? The Norman's justification for invading England was that Edward had sent Harold to Normandy with the explicit purpose of confirming William as the heir to his throne. Eadmer, who had access to people who might have known the full truth about Harold's journey, states otherwise and that Harold's sole reason for his journey to Normandy was to release his kinsmen. The images in the tapestry seem to follow Eadmer's version but without contradicting the Norman view. In the first scene, Harold is shown in a secret meeting with King Edward. If we are to follow Eadmer's version, we can interpret Edward listening to Harold explain his plans to visit William of Normandy to negotiate with him the release of his kinsmen. However, if we wanted to, we could also follow the Norman. Edward is discussing his request for Harold to visit his second cousin accross the sea to bestow his good wishes and confirm his heirship. Neither tale can be contradicted in the images.

Monday, 23 April 2012

The Mystery Woman of the Bayeux Tapestry: Part Six

Read the final part of this mystery on Sons of the Wolf Blog http://paulalofting-sonsofthewolf.blogspot.co.uk/2012/04/mystery-woman-of-bayeux-tapestry-part.html

And find out my final conclusion

And find out my final conclusion

Wednesday, 11 April 2012

The Bayeux Tapestry: A Tale of Two Men

As we know, the tapestry is an embroidered work, created in the 11thc to convey the story of the events that led to the Norman Invasion of 1066. The main characters of this saga are Harold Godwinson and William, Duke of Normandy. It is a tale of two halves, the first half appears to be from Harold’s perspective and the second is more from William’s. Before their fateful meeting in 1064, there does not seem to be any recorded documentation that they ever met prior to this. William is only recorded in one English source as ever having been to England, as stated by Douglas (1953) and Harold was at this time, in Ireland in exile.

William, known as the Bastard and later known as the Conqueror, was born in Normandy around 1027, the baseborn result of his father, Duke Robert of Normandy's liaison with Herleva, the daughter of a tanner. Robert never married William's mother, although he may well have had some regard for her, for she also bore him a daughter, Adelaide. Because of her status, he would not have been permitted to marry her and eventually put her aside, finding a husband for her, one of his barons Herluin de Conteville. Herleva went on to give birth to two sons, Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Robert the Count of Mortain and another daughter whose name is not recorded.

William was said to have been around 5ft 10 according to an examination of his femur bone, quite a tall man for his day. He was also said to have been strong, broad-shouldered and a strong bowman (Bates 2001). His voice was said to have been gruff and he seems to have had little in the way of culture. He was said to have not been able to read or write, in contrast to Harold who was a very well educated man. During his later years, he became very corpulent. Perhaps this was to compliment the avaricious reputation he had earned for himself.

Harold Godwinson

Friday, 23 March 2012

Aelfgyva: The Mystery Woman of The Bayeux Tapestry Part Five

We are getting closer to the end of this discussion, but I have by not finished it by a long shot. For those who have not read any of my earlier posts about this puzzling enigmatic woman, Aelfgyva, whose image is portrayed in the tapestry with a priest, we have been exploring her possible identity in an effort to ascertain who exactly she was. Furthermore, it is my aim to try and shed some light and interpret what or how she came to be sewn into this tragic tale about the story of Harold’s fateful trip to Normandy. After discounting the known candidates except for one, it would appear that the identity of this Aelfgyva is Aelfgifu of Northampton, as she was generally known according to one of the Anglo Saxon chronicles, in the early 11thc when she lived. She was a consort of Cnut, enjoined to him in the more danico tradition. Marrying her in this way meant that Cnut could take another, more politically convenient wife at a later date, as he did when he married Emma of Normandy, whose English name was also a Aelfgifu.

Aelfgifu of Northampton was the daughter of Aelfhelm, a major ealdorman of Northumbria whose familial origins were from Mercia. His mother was a wealthy woman named Wulfrun and I have not been able to find a source for his father, perhaps his mother was of higher standing. Regardless of her grandfather’s status, it was obvious that Aelfgifu came from a very important family. Her father was put to death by his enemy Eadric Streona and her younger brothers were blinded. All this was done with the connivance of King Aethelred. Aelfgifu may never have forgotten or forgiven this deed and it quite possibly could have shaped her personality from then on.

Because of her father’s status in the north, Swein of Denmark may have sought an alliance with her kinsmen and father’s followers, taking advantage of the rift Aelfhelm’s death may have caused between them and Aethelred. So she was either loosely married or handfastened to his son Cnut.. This was not an unusual practice, some years later Harold Godwinson was to do the same with his longtime love, Edith Swanneck. Many years later her puts her aside and marries the daughter of Alfgar of Mercia, wife of Gruffydd of Wales in order to enlist the support of her brothers, Edwin and Morcar who were earls of the north. The Normans were to make much of this when their propaganda machine got their claws stuck into Harold. He was promulgated as an adulterer who liked women although he seems to have stayed faithful to Edith Swanneck throughout their time together. They referred to her as being his mistress, although in legal terms she was considered his ‘wife’ and his children were treated as legitimate. However, perhaps she was not cast aside quite in the manner one would think, for legend alludes to her having been on the battlefield looking for his mutilated body at Senlac. This may have meant that their relationship was still very much an entity at Harold’s death.

Handfastened wives perhaps were not necessarily cast off when the man married politically and the evidence is inclined to show that like Harold may have done, Cnut kept his affections for Aelfgifu and did not wholly put her aside for Emma. In fact initially, he may have considered her with great respect, if not affection. She had given birth to two sons, Swein and Harald, named in respect for Cnut’s father and grandfather. When Swein was old enough, Cnut sent Aelfgifu with him as regent to rule for him in Norway around 1030. He may have done this to keep her out of the way of his relationship with Emma, though this is not founded in any source, but one can picture that the two women were serious rivals for Cnut’s affection and that they probably felt threatened by one another. On the other hand, Cnut may have simply been keeping the interests of the Northern thegns alive by continuing to honour her and the alliance with her family. Emma may have had the upper hand, however, being the recognised queen. And it is natural to think that Emma, an astute woman that she was, would not have agreed to marry Cnut if her children by him would not have had precedence over Aelfgifu’s.

One might have been forgiven for intuitively assuming that the nature of Aelfgifu of Northampton’s character was somewhat harsh when some four years later she and Swein had to flee Norway for her apparent heavy-handed rule. The Norwegians rebelled against her heavy taxation and it seemed, preferred Magnus I as ruler to Cnut’s harridan. Her son, young Swein, was to die in Denmark shortly after. In the Norwegian Ágrip Aelfgifu is mentioned by the Skald Sigvatr, a contemporary of her’s:

Ælfgyfu’s time

long will the young man remember,

when they at home ate ox’s food,

and like the goats, ate rind

She may have died sometime around 1040. Nothing much was heard of her after this. The story about her deception of Cnut is strangely alluded to in the Anglo Saxon chronicle, Abingdon edition (C) where it is mentioned: “And Harold, who said that he was the son of Cnut – although it was not true-..” This appears to be referring to the story about Aelfgifu’s sons not being Cnut’s, or indeed not even Aelfgifu’s. In my search for the truth, I have discovered that the Encomium Emmae Reginae makes the allegation that Harold was really the son of a servant girl smuggled into Aelfgifu’s bed chamber and passed off as Cnut’s son. John of Worcester elaborates further and tells us that Cnut’s sons by Aelfgifu were not his or hers even. That Aelfgifu, desperate to have a son, ordered that a new born son of a priest’s concubine be presented to Cnut as his own son by her. This was the child called Swein. Harold, he states, was the son of a workman, like the one seen in the border underneath Aelfgyva’s scene in the tapestry (Bridgeford 2002). Bard McNulty (1980) first drew the patrons of the Tapestry to the theory that this was Aelfgifu of Northampton. Bard McNulty also theorizes that William and Harold had a discussion in the previous scene whereby Harold reassures William that the English will not call upon Harald of Norway to become King when Edward dies. I have already rejected this theory because apart from her connection with Norway where Harald Hardrada invades England from in 1066, her connection to Harald Hardrada is neither tenuous nor nonexistent.

What I do, however agree with is Bard McNulty’s idea that the Aelfgyva scene is not meant to be read as what is happening after the scene before it, rather that it represents what they were discussing, an issue involving a priest and Aelfgyva. So, if they were not discussing Harald Hardrada, then what were they discussing about Aelfgyva and the priest? And what had it to do with the tapestry and Harold’s time in Normandy?

Look forward to the final conclusion in Part Six where I will explain what my theory is.

to view previous posts check out these links

to view previous posts check out these links

Friday, 24 February 2012

Tuesday, 3 May 2011

Aelfgyva, the mystery woman of Bayeux: Part One, 2nd ed.

Aelfgifu, or as it was sometimes spelt

Aelfgyva, must have been a popular name and one of some significance, for when

Emma of Normandy was espoused to Aethelred, the witan insisted that she be

called Aelfgifu, which incidentally had been the name of a couple of Aethelred's

previous consorts, though none of those women had been given the title of

queen unlike Emma. Perhaps they had been

so used to referring to their king’s women by the same name they thought it more

expedient to refer to Emma as Aelfgifu too, lest they forget themselves and

mistakenly call her Aelfgifu anyway. I say this tongue in cheek, but it is

unclear as to why the name Emma was objectionable to them, after all, it was not

unlike the English version of Ymma. But changing a queen's name is not an un

heard of phenomenon; later Queen Edith, great-granddaughter of Edmund Ironside,

was sneered at for her Saxon name and was forced to become Queen Mathilda when

she wed Henry the first.

There were so many Aelfgyvas/ Aelfgifus amongst the women of the 11thc that it must have become quite confusing at times. Even Cnut's first consort was called Aelfgifu, mother of Cnut's sons Harold and Sweyn. She was known as Aelfgifu of Northampton whose father had been killed during Aethelred’s reign. So one can see that if anyone called Emma, Aelfgifu, by mistake, it would not have mattered as they could be referring to either of them! Even Cnut would not have been caught out by this one.

There were so many Aelfgyvas/ Aelfgifus amongst the women of the 11thc that it must have become quite confusing at times. Even Cnut's first consort was called Aelfgifu, mother of Cnut's sons Harold and Sweyn. She was known as Aelfgifu of Northampton whose father had been killed during Aethelred’s reign. So one can see that if anyone called Emma, Aelfgifu, by mistake, it would not have mattered as they could be referring to either of them! Even Cnut would not have been caught out by this one.

There was a story about Cnut's Aelfgifu, that she

had been unable to produce her own off-spring and involved a monk to help her

pass off a serving maid's illigitemate babies as her sons by Cnut. In another

version, it was said that the monk himself had fathered them himself. Were they

a monk's children fathered on a serving maid so that Aelfgifu could present them

as hers and Cnut's? Or, were they lovers themselves, the monk and Aelfgifu?

These are questions that, after reading the evidence, I am pondering upon.

However, Emma, it is said, hated Aelfgifu and the two women were at odds with

each other for many years until Aelfgifu died. It would not be implausable that

these tales, rumours, chinese whispers if you may, could have been put about by

the Queen to destroy her rival's reputation.

Which leads me now to the mystery of Aelfgyva on

the Bayeux tapestry. Aelfgyva is the same name as Aeflgifu only a different

spelling, much like Edith and Eadgyth. For centuries people must have pondered

over this scene, where a slim figure, clad in what would appear to be the

clothing of a well-bred woman stands in a door way, her hands are palm upwards

as if she could be explaining something to a monk, apparently behind the door.

He is reaching out to touch the side of her face whilst his other hand rests on

his hip in a stance of dominance and he looks as if he might be touching her

face in a fatherly way, perhaps admonishing her for some misdeed, or perhaps he

is slapping her? On the other hand he

could be caressing her face. The text sewn into the tapestry merely states

‘where a priest and Aelfgyva...’ and the onlooker is left with no more than this

to dwell on. So just what is the author alluding to? Why did he/she not finish

the sentence? Perhaps they were referring to a well known scandal of the time

and they had no reason to describe the events because everyone would have known

about it anyway. Who knows what the truth is? It seems the answer to the

questions of the lady’s identity and the relevance the scene has to the story of

the downfall of Harold Godwinson, died with the creators of the tapestry long

ago. Those who presented it to the owner must have given a satisfactory

explanation to him about the scene. One can only wonder as to what it might have

been and was it a truthful explanation, or did it have a hidden

story?

This brings me to my burning question. Was this

scene depicting the scandal of Aelfgifu of Northampton and the monk and if so

why and what did it have to do with the tapestry? What was its creator alluding

to? Or had someone woven them into the tapestry, mistakenly confusing Cnut's

Aelfgifu/Aelfgyva with a similar story that did have some legitimacy with the

story of the conquest? I have an interpretation, but it is just that, and most

likely the fanciful ramblings of my imagination, although it could perhaps be

close. I will attempt to explain my theory further sometime in part two soon.

Watch this space as the mystery unfolds!

More about this post on my Sons of the Wolf blog

Monday, 20 February 2012

The Origins of the Bayeux Tapestry

|

| Add caption |

Welcome to the first post on Threads to the Past, my

blog about mysteries of the Bayeux Tapestry. This post is devoted to the

Tapestry itself, where it came from and the possible commissioners. This seemed

a very good place to start this blog, at the beginning. Firstly, unlike its description,

it is an embroidery as I am sure most of you have realised. I have no idea why

it was mistakenly called a tapestry and frankly, I don’t think it is necessary

to go delving into that one, however the Bayeux Embroidery doesn’t have quite

the same ring to it as the Bayeux Tapestry, probably because we are so used to

it being called that. A tapestry is an entirely different thing altogether from

a tapestry which is an image woven into the material rather than embroidered

upon a piece of material.

|

| The Bayeux Cathedral |

The tapestry is a long piece, around 70 metres long

(230ft) with woollen threads embroidering the linen background. The width of the

embroidery is around 0.5 metres (1.6ft). Around 50 scenes decorate it with

inscriptions written above some of images in Latin. There have been later

restorations to the embroidery and in 1724 a backing cloth made of linen was

sewn on to it to perhaps protect its fragility. Later, numerals were to be

written on the back in black ink to numerate each scene, obviously by someone

who was studying it and wanted to create some order to it.

Housed in the beautiful city of Bayeux with its gothic

Cathedral at its centre, it is known by its signs as simply the ‘Tapisserie’ and also in English. It is

kept in a 17thc building that was converted into a museum in the early ’80’s.

Confined carefully inside a glass casing, cautiously illuminated, it stretches

out around the narrow corridor and plays out like the scenes from a cartoon. This

amazing piece of history has survived the passage of more than 900 years not

without some damage, but most of it is entirely original (Bridgeford 2004).

Its first factual reference was in 1476 when it was

amongst the inventory of the Bayeux Cathedral (Wilson 1985). The fact that it

has remained so well preserved since around 1070 is in my opinion a miracle. How

many others of this type on such a grand scale can there be? None to my

knowledge unless anyone can put me right. It has even survived the 1562 sacking

of the Huguenots when they stormed through the cathedral where it was believed

to have been stored, burning and smashing most of the items listed in the

inventory of 1476. Due to the swift thinking of the clergy, they managed to

secrete some of the items away after a tip off and thus the beautiful

masterpiece survived. It also managed to

survive the Second World War when the Nazi’s took the tapestry to study it,

believing it to be a great monument to Germanic domination rather than to

French national history (Brown 2012).

So how did this embroidery that describes an

English/Norman event find its way to Bayeux? How did it survive all these years

and who commissioned it to be made and whose fingers created it? What are the

stories depicted upon it and who were the players?

These are all questions I intend to explore in this

blog. Excited? I am.

Welcome to My New Blog

Welcome to my new blog, THREADS TO THE PAST about the mysteries and tales embroidered into the Bayeux Tapestry. My name is Paula Lofting Wilcox and I am the author of Sons of the Wolf which is my novel set in the 11thc about the fortunes of Domesday man, Wulfhere of Horstede. I started posting various snippets of factual events, people and stories on my Sons of the Wolf blog and thought it may be more of interest to people if I created a seperate blog for the Bayeux Tapsetry aftert I started my posts about the mystery lady, Aelfgyva on the BT. I had intended to make these posts into three parts but the more I investigated the mystery, the longer the threads became. Then I realised that there was a lot more interesting tales illuminated in the threads of this amazing embroidery and felt compelled to create a blog that would be solely dedicated to the history stitched into the fabric of life as it was in 11thc Englalond.

Please join me as I begin the journey and come with me to meet characters like Edward the Confessor, his wife Edith Godwinsdottir, her brother Harold and his arch rival William of Normandy and his brother Odo, the bishop of Bayeux and Eustace of Bologne and many more. You can also learn what facts my investigations into the mystery woman Aelfgyva have turned, learn who she might have been and about what was her role in the story of Harold's fateful mission to Normandy.

I look forward to having your comapny on what I am sure will be an exciting ride.

Link to my blog Sons of the Wolf http://www.paulalofting-sonsofthewolf.blogspot.com

Labels:

Aelfgyva,

Bayeux Tapestry,

Bishop Odo,

Edith,

Edward the Confessor,

Eustace of Boulogne,

Harold Godwinson,

Threads to the Past,

William of Normandy

Location:

Crawley, West Sussex, UK

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)